“… long, sorry decline has left the 140-year-old company a shell of its former self. Today, it is fighting for its very survival. Western Union fell victim to technological advances…”

Associated Press, 1991

Reading current reporting about Western Union’s role in international remittances could make us think that the company has been a successful monopoly in this space forever. Still, with the arrival of some disruptive innovations (“P2P”, “Bitcoin-stablecoin,” “Social,” “Mobile,”…), there is a real danger of its imminent demise. In reality, Western Union’s subsidiary, Western Union Financial Services Inc., began providing international money transfers in 1982 thanks to deregulation. By the mid-90s, Western Union’s coverage included major remittance destinations, such as China. In those initial years, Western Union (renamed “New Valley” in 1991) experienced numerous upheavals, coming close to or even entering bankruptcy. After changing hands a few times, the money transfer subsidiary was resurrected as an independent entity in 2006. Western Union’s stock performance has been highly volatile ever since, dwarfed by the overall market:

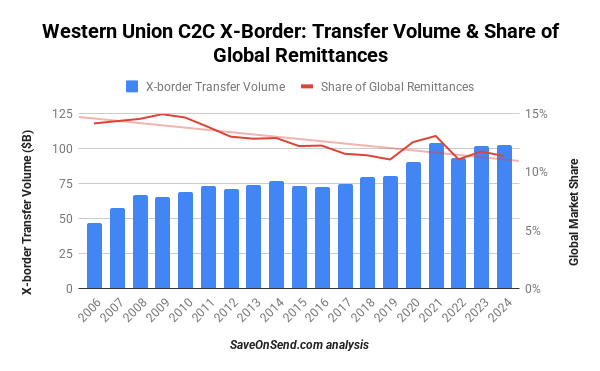

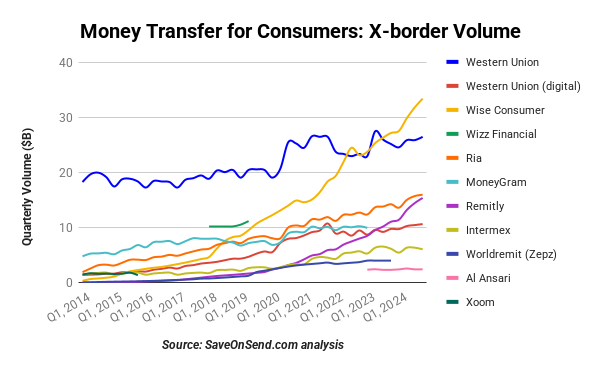

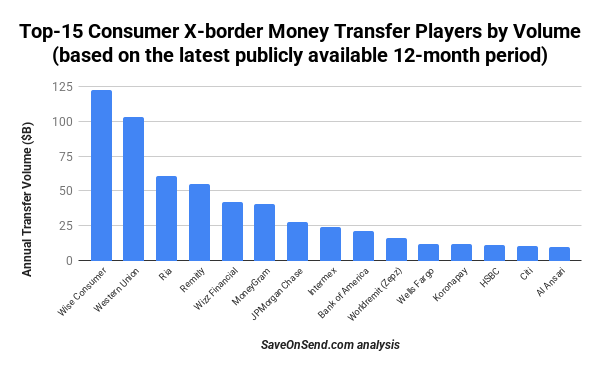

After growing till 2011, Western Union’s transfer volumes remained stagnant till 2019, even as the remittances market grew by over 40% during the same period. Volumes temporarily picked up in 2020 as Western Union’s digital channels gained scale due to COVID-19 restrictions. However, despite this one-off uptick, the lower margins of digital transfers resulted in overall static revenue over the last decade.

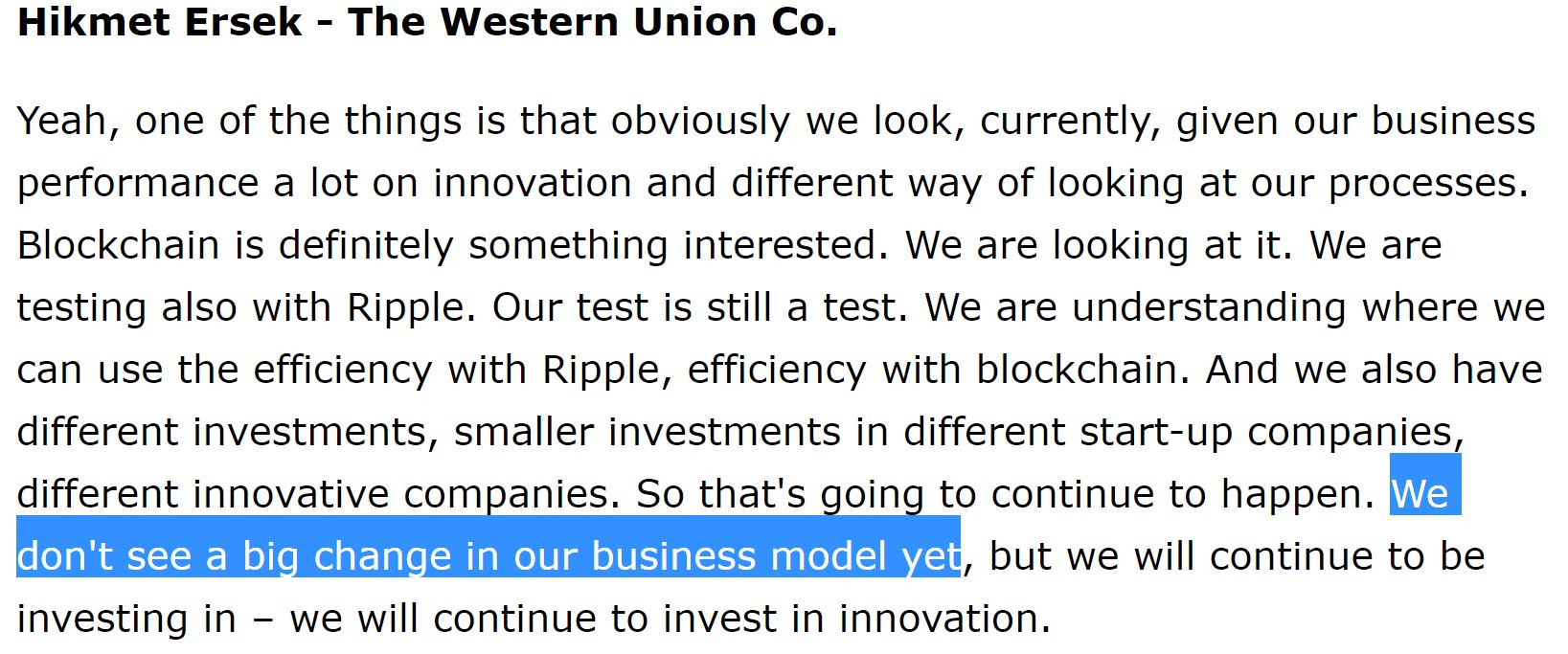

Western Union’s disappointing performance is no surprise, given its history of complacency about fintech disruption. In a June 2019 interview, a senior executive brushed off Fintech competition:

In a counterproductive move in 2019., Western Union closed its digital office in San Francisco as part of an enterprise-wide cost-cutting initiative to centralize activities in fewer, more cost-effective locations. Besides the extended development time for its digital strategy, Western Union also took nearly a decade to strengthen its compliance and risk management, finally settling the last FTC lawsuit in January 2017.

“Even though Western Union’s internal reports have identified agent locations where 5% to over 75% of the transactions constituted confirmed and potential fraud, and/or suspicious activities, Western Union has allowed many of these agents and subagents to continue operating, with only temporary suspensions, if any…”

As Western Union’s valuation has declined to below $4 billion, its story of ups and downs has become less captivating to the media. Gone are the times of regular sensational reporting of Western Union’s likely demise, attributing it to the latest innovation du jour, be it Facebook, fintechs, or Bitcoin.

1. Western Union’s Market Share

Western Union’s market share is complex, as is much of the international consumer remittances. Since 2009, the company has been gradually declining as it has struggled to keep pace with the growing, ever-more intricate cross-border consumer money transfer market.

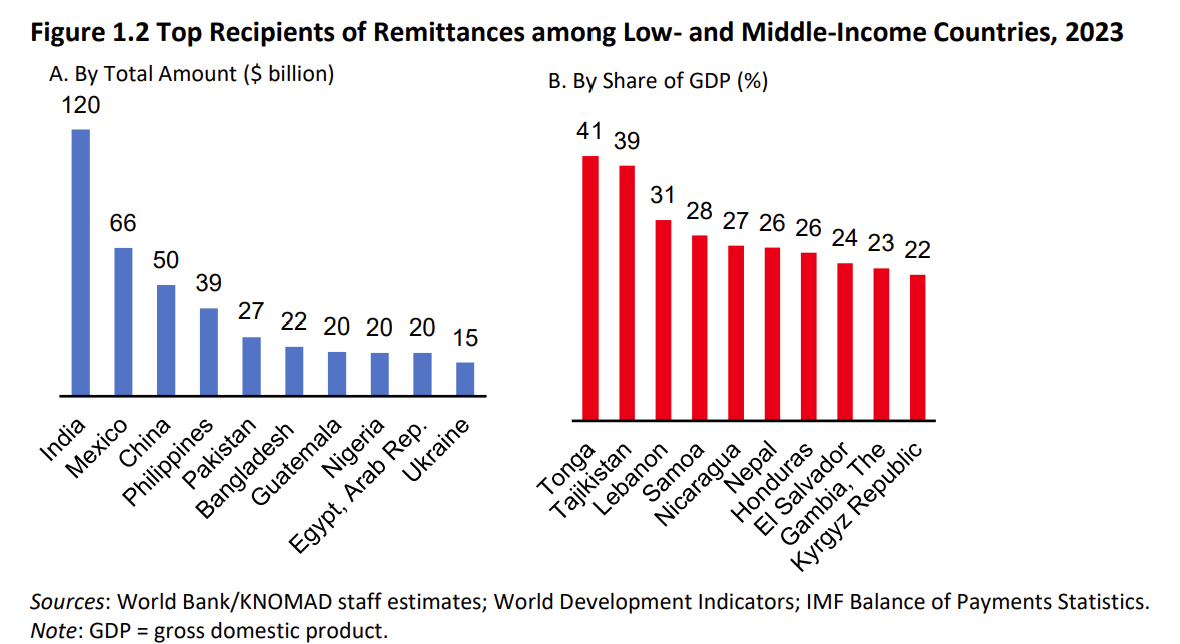

The remittances market’s remaining share is highly fragmented, with numerous banks and MTOs of varying sizes competing in each major corridor. Western Union’s market share is also not evenly distributed across global corridors. For instance, historically, in the world’s largest remittance corridor, USA-to-Mexico, Western Union’s market share has been closer to 20%.

Source: SEC

Western Union’s market share is below 10% in several large corridors, while in some smaller corridors it approaches 50%. Criticizing Western Union for offering services in places with little to no competition would be akin to labeling a single gas station in a small town a “monopoly.”

2. Western Union’s track record of innovation

While many Bitcoin and FinTech startup enthusiasts love to recount Western Union’s rejection of the “talking telegraph” in 1876, they often overlook that the company maintained a telegraph monopoly for the next 100 years and introduced numerous innovations during that period.

While PayPal pioneered email transfers in 1999, Western Union quickly embraced the online world in 2000, forged mobile partnerships in 2007, and launched a smartphone application in 2011—before TransferWise and Remitly were even on the scene. Despite TransferWise’s savvy use of data to drive referral traffic and Remitly’s “mobile” innovation, Western Union has been at the forefront of adopting cutting-edge technologies. Its extensive use of “big data,” exploration of a partnership with Ripple Labs, and investments in blockchain all debunk the popular narrative that labels Western Union as backward and ignorant.

Adding to its list of achievements, Western Union was the first to forge partnerships with WeChat and Viber. Why would such innovative providers choose to partner with Western Union? While the company’s technical capabilities in executing complex integrations are unmatched, the primary reason lies in consumers’ trust. Western Union has enjoyed confidence that few can match regarding money transfers.

Here is how Western Union’s former CEO described the company’s approach to innovation in May 2018:

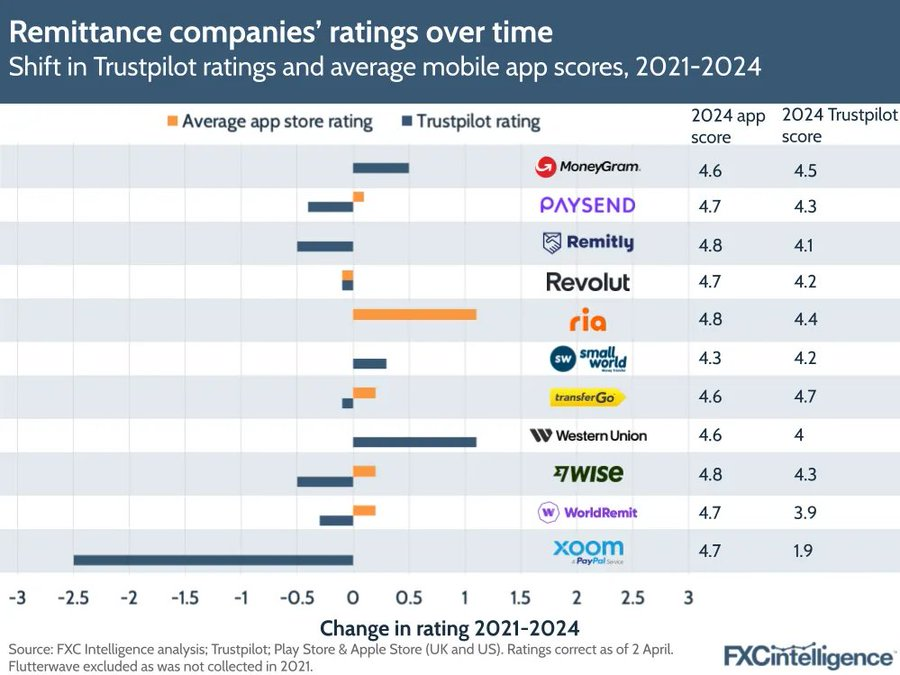

Western Union’s mobile application rating and customer reviews are also on par with leading fintechs:

It is also essential to consider that 80% of new Western Union digital customers are entirely new to the company, having never used Western Union in any capacity. This indicates relatively little cannibalization, around 2%, from Western Union’s offline to digital channels. Instead, the company successfully attracts entirely new customer segments. Contrary to the myth fueled by Fintech PR, actual demographics segmentation of customer bases for incumbents across financial services shows that so-called “millennials” exhibit a similar preference for trusted brands (aka “incumbents”) as other generations.

Western Union introduced an innovative approach and achieved significant growth in online engagement by developing dedicated Facebook pages for Filipino, Indian, and Latino customers.

Western Union’s digital transformation extended beyond customer engagement. Between 2016 and 2017, the company invested $120 million in “WU Way,” an efficiency program primarily focused on severance (40% of all costs) and consultants (25% of all costs). The objective was to digitize operations, consolidate offshore IT locations, and reduce staff, aiming to achieve $20-25 million in annual savings.

By April 2019, Western Union’s outbound digital services were available in 75 countries, with its mobile apps accessible in 35. The company expanded its digital footprint, onboarding 20 countries by 2010, 23 in 2011, only 2 in 2012-2014, 9 in 2015, and 20 in 2018. Of course, the US remained Western Union’s top focus, so, despite this global expansion, Western Union’s international share of consumer cross-border revenue has remained relatively stable at around two-thirds.

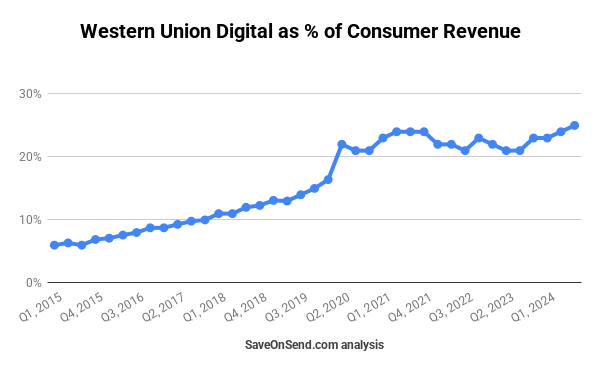

By 2019, Western Union’s digital footprint covered over 95% of the world’s outbound sending countries by transfer volume. The remaining countries were either too small or subject to government regulations that prohibited online remittances. However, the primary challenge for digital transfers was the slow change in the habits of money senders. Despite 70+% of Western Union customers having bank accounts, it took a global pandemic to witness a one-time acceleration in the adoption of digital transfers:

The slower adoption of digital channels in cross-border money transfers isn’t due to an inadequate digital offering but rather to significant variation in digital usage across specific corridors, or, more precisely, by ethnicity. Major migrant groups in the US, such as Indians, Filipinos, Chinese, and Mexicans, have distinct financial behaviors. For example, Indians, often in white-collar jobs, tend to have a high ratio of disclosed income. In contrast, other nationalities are more likely to be in the country without a visa and to be paid in cash for blue-collar jobs such as babysitting, construction, or driving cabs. Since regulators don’t require strict KYC for cross-border cash transfers below $3,000, this dominant segment of US remittance customers remains inclined to use offline channels.

Even before establishing a dedicated online unit, Digital Ventures, in San Francisco in 2011, Western Union’s digital business was already on par with Xoom, a digital-native competitor, in terms of transfer volumes. However, it has struggled to achieve rapid global growth. While Western Union’s digital business grew at an annual rate of around 20% until 2021, growth has stalled since then, while newer global leaders like Wise and Remitly continue to increase by 20-40%.

3. Western Union’s offline performance.

In the offline world, Western Union’s agent network expanded from 200,000 agents in 2006 to 485,000 in 2011. However, the growth rate slowed significantly; by 2017, the number had only increased to 550,000. The slowdown in adding new agents can be attributed to around 30% of existing agents already not seeing any remittances, as reported in the 2016 annual filing:

“As of December 31, 2016 , more than 70% of our locations had experienced money transfer activity in the previous 12 months”

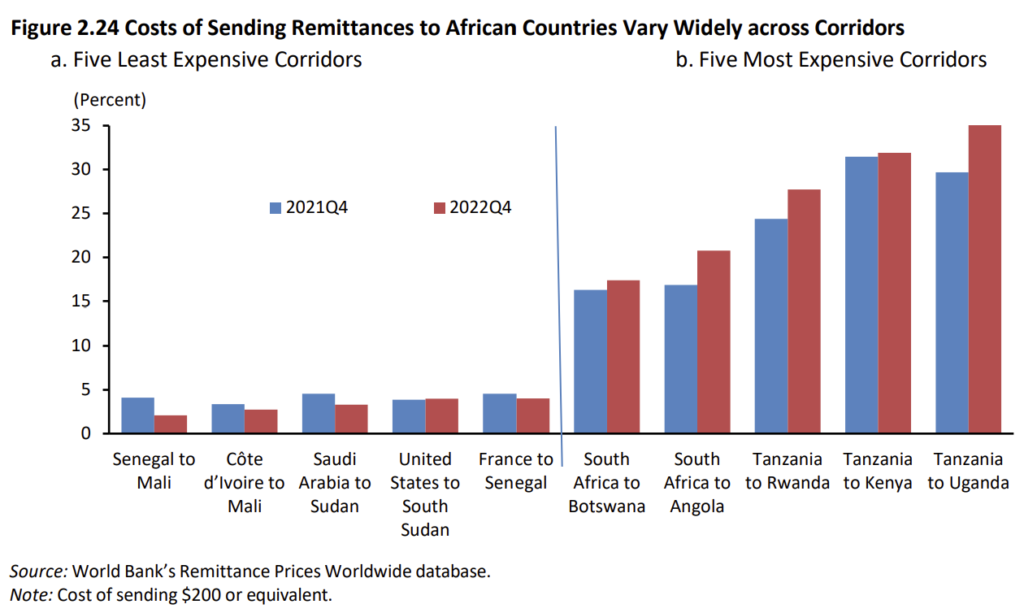

Western Union is not unique in its business-savvy prioritization of where to offer its services. Despite fintech remittance startups’ posturing about helping the “poor” and “unbanked,” they often set up offices in the world’s wealthiest cities, targeting well-off and tech-savvy senders. These startups conveniently accuse Western Union of being a high-priced monopoly. Below, on the right, are some of the world’s most expensive corridors; one can check which startups offer services for them.

Talk is cheap, and venture capitalists can be very impatient. Selecting a smaller corridor with a small percentage of tech-savvy users may not seem lucrative enough. So don’t be surprised by how Remitly’s founder explained his motivation when launching the startup in 2011 vs. what he actually did (read the full story here):

Words like “kid,” “education,” and “Africa” were essential components of any pitch deck. Interestingly, in 2011, the only practical way to send money from the US to Kenya was to start another company. While one might have assumed Remitly would start with Kenya, it turned out the volume of remittances there was not substantial enough, and the market lacked the desired tech-savvy. Instead, Remitly began its journey with the Philippines, followed by India, China, and Latin America. Years later, the company expanded its outbound business beyond the US into Canada and the UK. It took nearly a decade for Remitly to finally make Kenya one of its available destinations.

This anecdote is relevant to our question about Western Union’s leadership position, as it exemplifies a common mindset among remittance startups. Instead of challenging Western Union’s market share in areas lacking an online presence, these startups tend to target the same “top” corridors where Western Union’s digital business is already well-established. This approach highlights the intense competition for a share of the same customer base, which has obviously impacted Western Union’s market dominance in the world’s top destinations.

Instead of Lagos and Sao Paulo, fintechs have opened offices in Denver and New York, coming to Western Union’s home turf.

4. Western Union’s competitive zeal

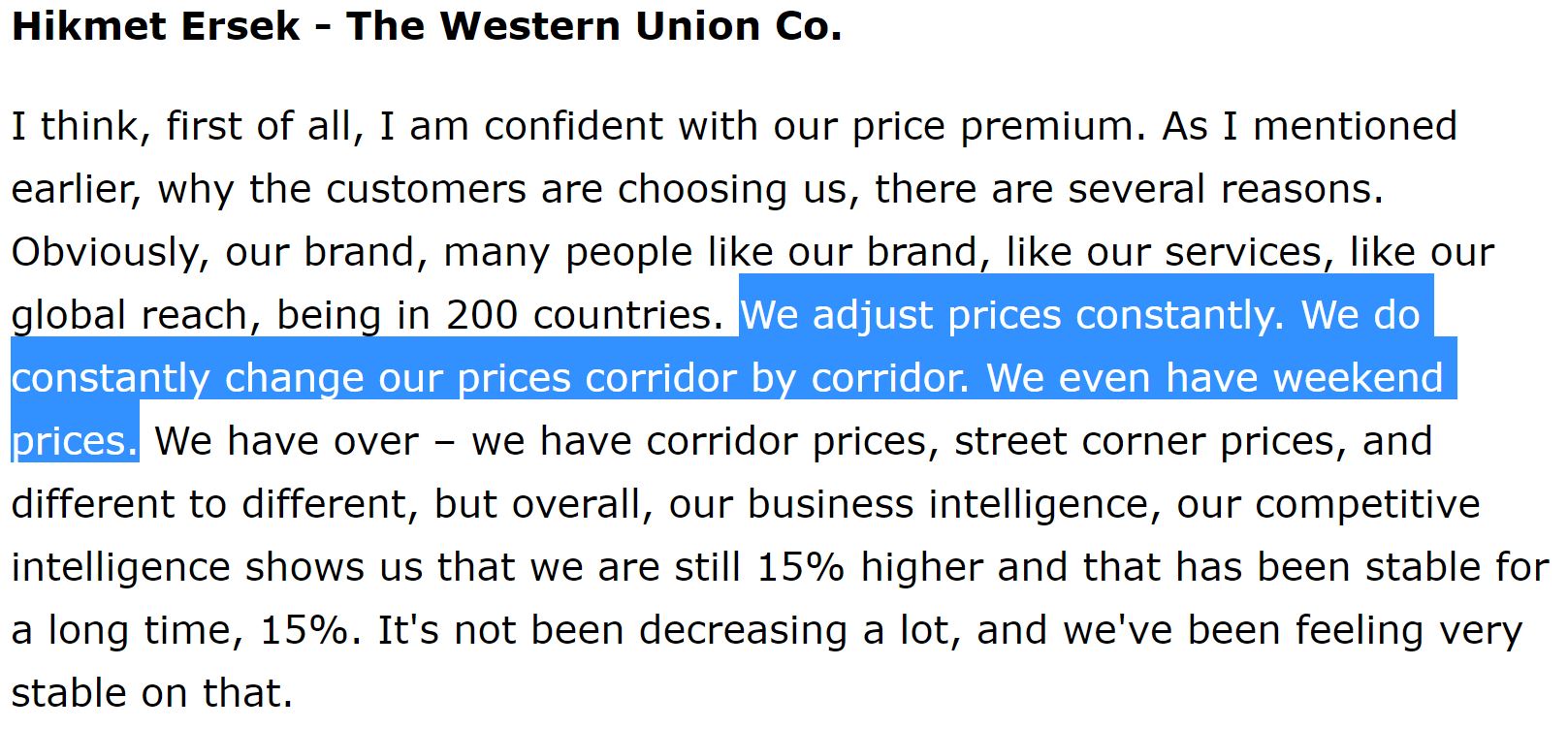

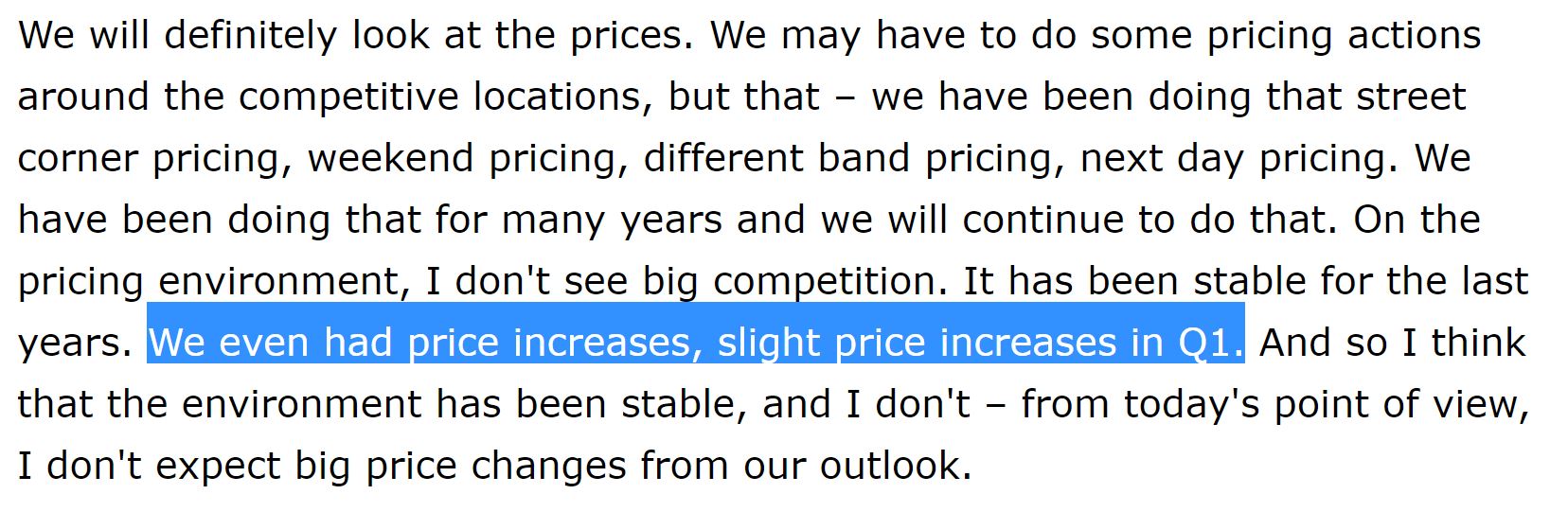

Western Union’s underwhelming performance is not due to a lack of effort that extends beyond innovation. Historically, Western Union has sought to command a 15% pricing premium for its brand overall, but It applies significantly different margins across corridors. The company frequently adjusts fees based on transfer amounts and send-receive methods, as described by Western Union’s former CEO in May 2018:

In 2020, Western Union acknowledged that it even adjusted pricing based on ethnicity, validating ethnic stereotypes about savings and comparison shopping attitudes, and demonstrating that such insights are used to make money at scale.

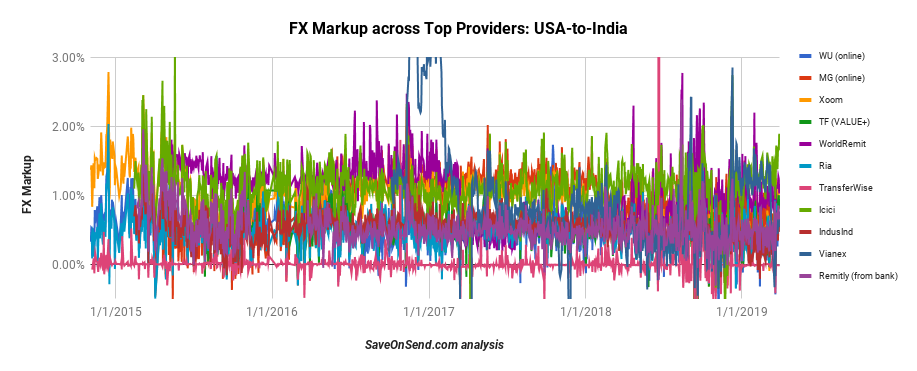

For example, Western Union’s FX markup for sending money from the USA to India was among the lowest among the competitors. Still, from the USA to the Philippines, it was one of the highest:

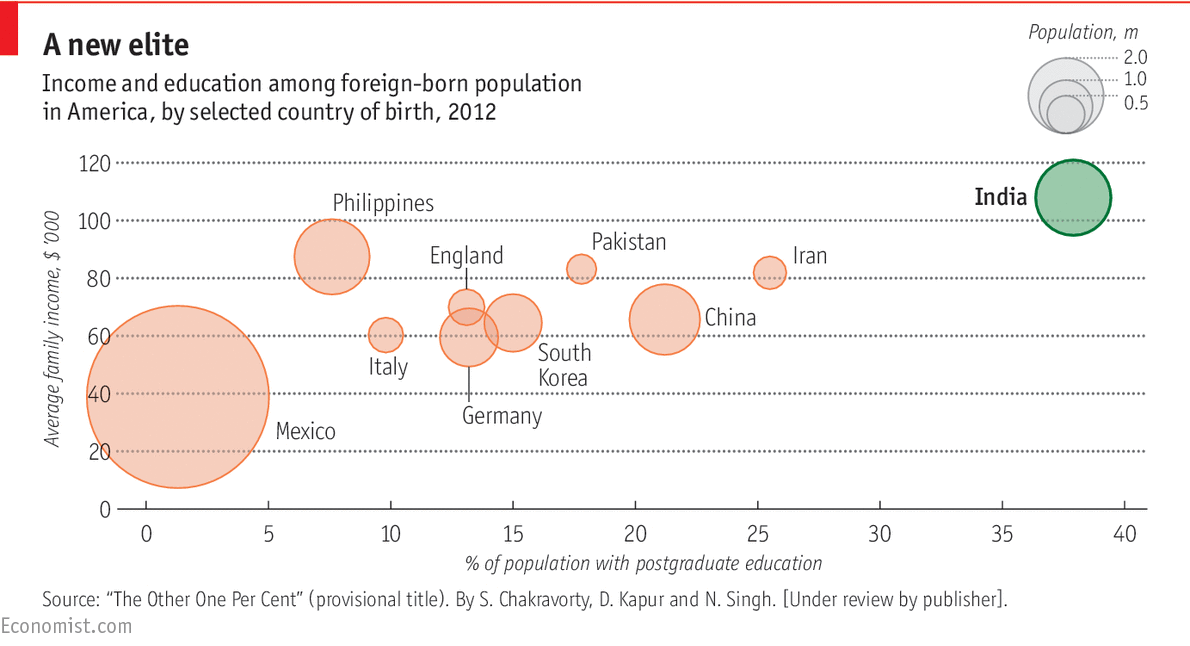

What could explain such differences in tactics for two corridors that are similar in size and located in the same region on a global scale? To understand this, let’s review the income and education levels of Indian and Filipino migrant groups living in the USA:

Indians are remarkably ahead of other main migrant groups in education, which sets them apart in their engagement with remittances. Over 80% of money transfers by this group in the US are conducted online. From a cultural standpoint, Indians are significantly more inclined to compare prices and switch providers, making their behavior distinct regarding remittance choices.

For other migrant groups, the average use of digital money transfers is around 30%, with Filipino senders from the USA showing slightly higher digital adoption. Additionally, other migrant groups exhibit less price comparison behavior and are less prone to switching providers. Consequently, Western Union is far more competitive in the USA-to-India corridor.

For example, upon noticing TransferWise’s (Wise) activity in the UK in 2017, Western Union reduced margins and offered specials to safeguard its market share. With Chinese customers, the challenge lies in a culture of secrecy and mistrust of formal channels. To gain a foothold in this segment, Western Union has, at times, offered literally free transfers for some send-receive methods to gain a foothold in this segment:

“…We do have corridors, which is zero FX. We do have corridors, which are higher FX, zero fees. We do have corridors where there’s both are that. It’s really like an airline management where you fly from one destination to another destination, which seats you for use, and that’s exactly what we are doing with our teams. I think, in the portfolio management, the team is impressive. It’s really looking at every corridor, understanding the customer needs on FX side.”

5. Western Union’s Future

Investors may experience “bullish” or “bearish” mood swings, but in the long term, only actual results, revenues, and profits truly matter. If you revisit the chart of Western Union’s stock prices since its IPO, you’ll notice three significant sell-offs—one during the 2008 financial crisis, the second when Western Union warned of sharp margin reductions in 2012, and the third since 2021, reaching new all-time lows in 2025.

After realizing the COVID spike was temporary, investors no longer believe Western Union can thrive against fintechs in the long term. Wise, Remitly, and countless other global and regional fintechs might not yet be poaching many Western Union customers. Still, they are clearly preventing Western Union’s digital growth while the offline channel continues to shrink.

But how did the Western Union lose its dominance? Like Xoom, Western Union had an early start advantage over fintechs but failed to transform its operating model to match startups’ effectiveness. By dismissing fintechs until a few years ago, Western Union’s leadership overlooked the compounding nature of high-growth rates in those startups. When such growth happens year after year for more than a decade, a tiny startup could catch up to a leader.

Here is again how nonchalantly Western Union’s former CEO viewed competition in 2018:

However, don’t expect Western Union’s demise anytime soon. When we see the long lines at overpriced coffee shops, it seems odd to consider those consumers victims of a traditional latte cartel that takes advantage of its customers with slow, expensive service. So why should we think differently about consumers who willingly stay in line at Western Union’s cash agents, pay more for the service, and prefer that experience?

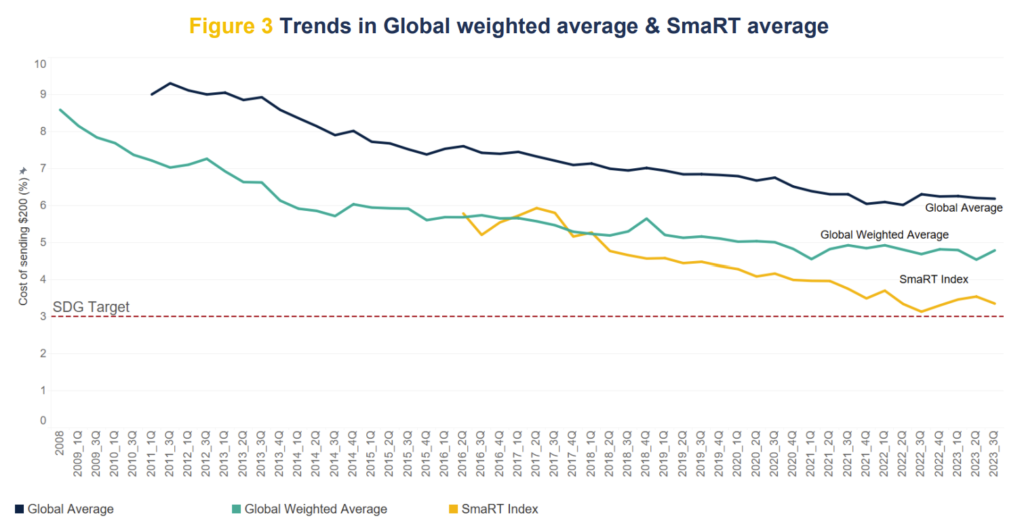

It wasn’t always the case, but today’s consumers are generally satisfied with their cross-border remittance options. There are a few complaints, half of which pertain to fraud (read the report here). Additionally, the margins in the industry have been steadily falling over the last three decades, experiencing a 40% drop in the previous 15 years alone, bringing them to less than 5% today:

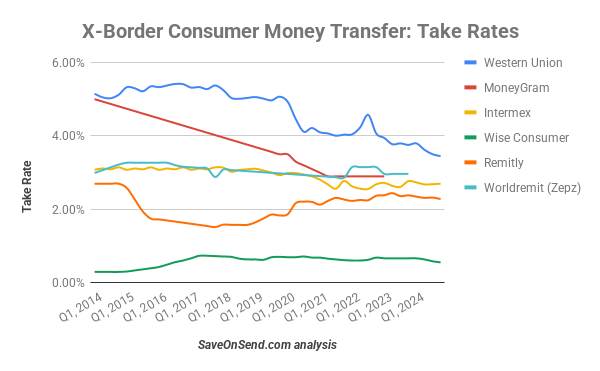

Western Union is undoubtedly, though somewhat reluctantly, part of the margin decline in the cross-border consumer money transfer industry. Its markup remained above 5% until 2019, gradually declining to under 3.5% due to a large share of less expensive digital transfers. Western Union will likely continue making reluctant changes to slow the decline in market share as the future unfolds. While it’s no longer the dominant leader it once was, Western Union is not in danger of being retired into oblivion anytime soon.

Conclusion

Hopefully, you found this overview helpful in developing your own perspective on Western Union’s chances of remaining among the top players.

We will be keeping this post regularly updated, so come back soon!