“The dogs bark, but the caravan moves on.”

Arab Proverb

The foundation of money transfer startups’ PR pitch centers on a relatively intuitive concept concerning the role of banks: they are massive institutions with bureaucratic cultures, subpar customer service, and outdated digital capabilities. Consequently, it’s only a matter of time before banks are displaced from the cross-border money transfer industry. Ironically, this premise holds. A typical bank is notably behind in service quality and pricing compared to the leading fintech startups. Furthermore, most banks don’t consider a money transfer business strategic.

Why Banks Don’t Take Money Transfers Seriously

It would be naive to assume that banks are not concerned about competition. In the United States alone, there are 4,000 banks and countless credit unions whose executives obsessively compare their strategies to local and national competitors. However, banks naturally view their competition pragmatically: “What are the top five reasons for revenue slowdown?” or “Which new business trend could jeopardize 10% of profits?”

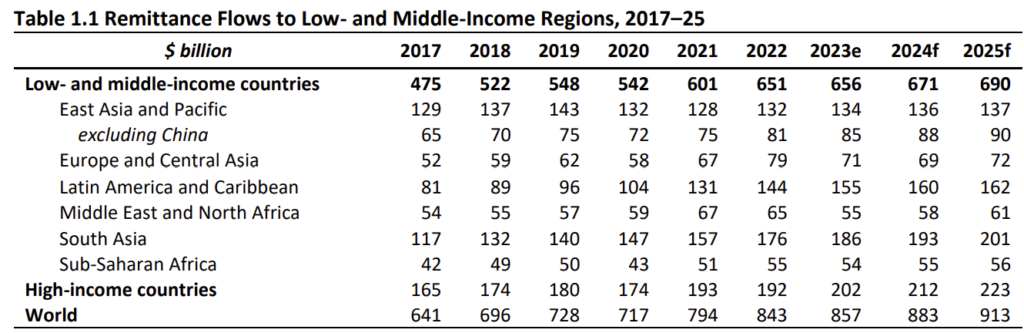

You have probably heard that the market size of consumer cross-border money transfer services is substantial. According to the World Bank, remittances alone amount to nearly $0.9 trillion, and the overall cross-border C2C volume is about twice as large.

However, given an average margin of less than 4%, even $2 trillion in volume would translate to approximately $70 billion in global revenues for the consumer cross-border money transfer industry. Since banks predominantly generate their revenue domestically, the portion of money transfer revenues relevant to banks is considerably smaller. The United States, the world’s largest outbound market for consumer money transfers, contributes about 20% of the global revenue, which amounts to around $15 billion.

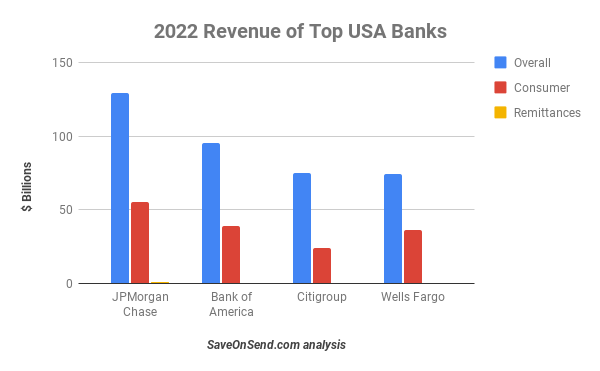

How does that $15 billion compare to the current revenues of the four largest US banks? Let’s examine the overall, consumer, and cross-border business revenues of these banks, all of which rank among the top 25 global banks:

If the above chart is magnified, the banks’ current remittances revenue becomes barely visible. It represents approximately 0.5% of the banks’ overall revenue or around 1-1.5% of their consumer banking revenue.

Courtesy of The Guardian, you can observe similar data for Santander, where all cross-border-related business represents around 1.5% of the bank’s total revenue (disregard the sensational and erroneous point about “10% of the Group’s profit):

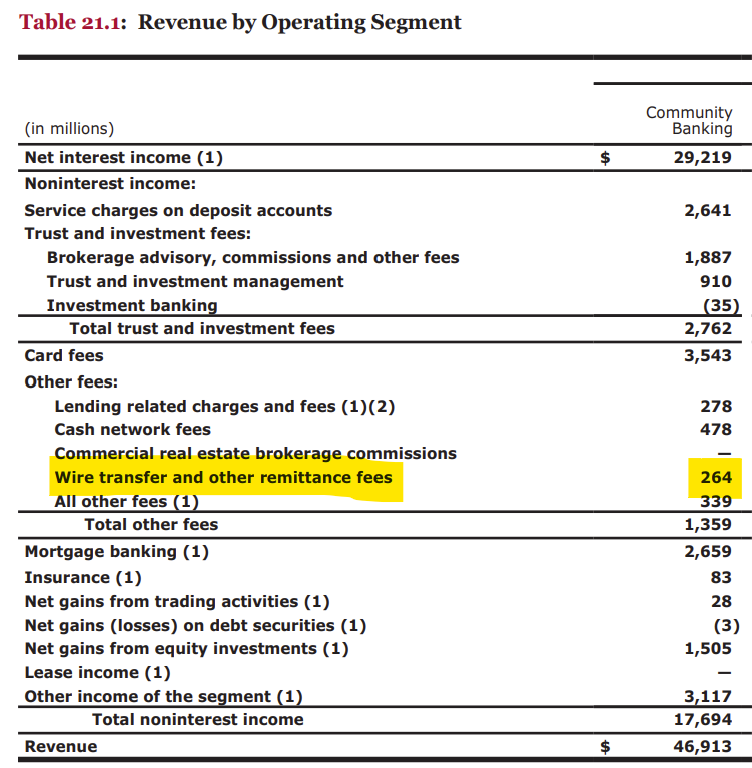

For Wells Fargo, cross-border money transfer fees are so minimal that the bank separated them for the last time in 2018:

Even if one of these banks were to miraculously become the sole provider of remittances in the country, displacing hundreds of competitors in the process, it would only gain an additional 10% on top of its consumer business.

Banks competitive position

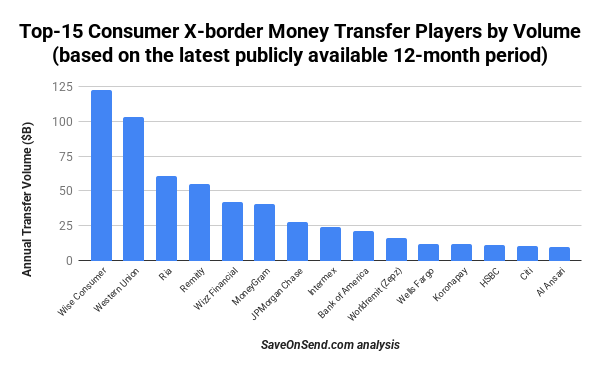

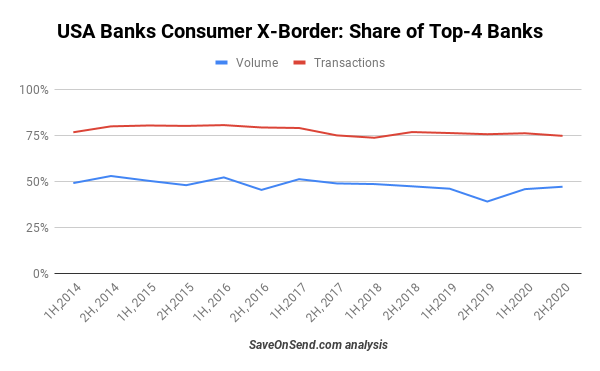

All US banks’ annual cross-border consumer money transfer volume totals approximately $150 billion, accounting for about half of the USA outbound volume. This figure encompasses all types of consumers, including the affluent clients of banks’ Private Banking groups. Such a significant market share of banks is not exclusive to the US. For instance, in the case of transfers from the UAE to India, a single bank, Axis, commands a 20% market share. Korea’s top 5 outbound money transfer providers are the country’s four largest banks and Western Union.

Now, let’s compare the size of cross-border global money transfer volumes between the banks and the cross-border specialists, also known as Money Transfer Operators (MTOs), including fintechs:

The largest banks in each country usually handle the majority of transactions and about half of the transfer volume out of the country:

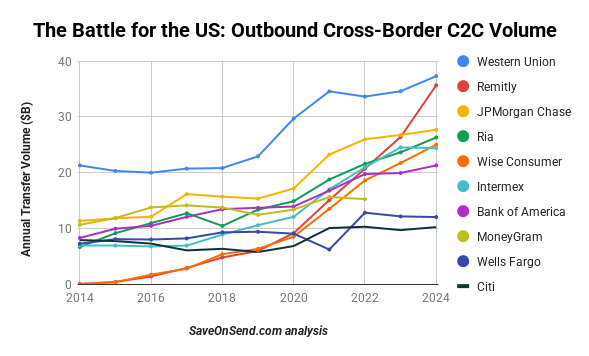

Top banks lag behind the leading specialists in transfer volumes, partly because they lack a consumer presence in many countries. However, within a single country like the US, the top two banks are not as far behind leading traditional MTOs and fintechs:

Notice on this chart that in a decade, the four largest banks in the US have doubled their collective transfer volume, outpacing Western Union’s growth. However, smaller MTOs, especially fintechs, have grown much faster during the same period. In less than fifteen years since launch, Remitly transfers more volumes out of the US than any bank, and Wise is not far behind.

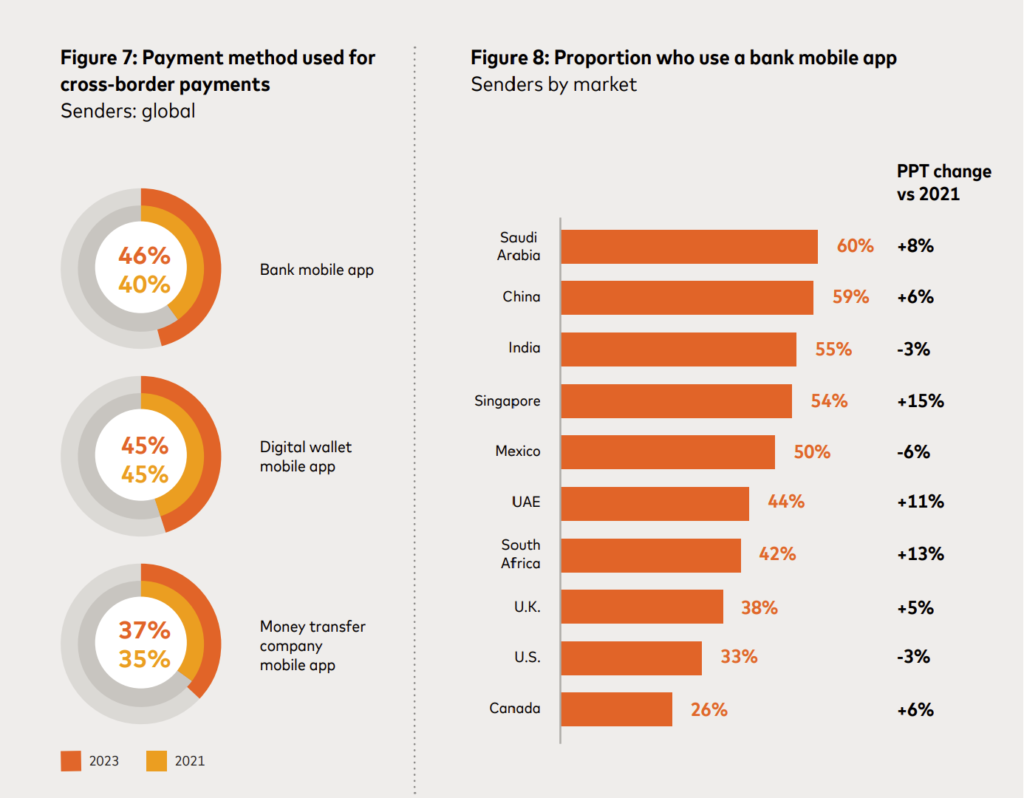

Top banks not only remain among the top 10 outbound players within each country despite the growth of fintechs, but are also becoming more digitally mature. Between 2021 and 2023, bank mobile app usage for remittances grew the most compared to wallet and money transfer apps, making it the most used app among these three groups:

What Banks Don’t Like About Consumer Cross-Border Money Transfers

Besides being a minor bank revenue source, cross-border money transfer has become increasingly challenging. As outlined in another SaveOnSend article, regulations designed to combat terrorism financing, money laundering, and tax evasion, while necessary, have also imposed significant resource and system investments on service providers.

This burden is twofold for a large bank: offering customers cross-border money transfers and banking services to Money Transfer Operators (MTOs). The latter business has become exceedingly complex from a compliance perspective, leading banks en masse to close accounts of money transfer providers, a global trend known as “de-risking“. In essence, the profits banks earn from serving MTOs do not offset the additional investment requirements and legal exposure created by regulations. Here’s how a senior banker privately describes the risks associated with holding a correspondent account for a large remittance company (“XYZ,” to maintain anonymity):

“We have an acute concern with a regulatory actions against our bank if XYZ’s x-border client commits an illegal activity. To manage risk exposure, our bank conducts an annual two-full-day dedicated compliance due diligence on XYZ with AML, Compliance, Payments committee members and stakeholders from Risk, Banking and Cash Management teams. One of top priorities is to ensure that we are only enabling business accounts transfers for XYZ and that those transfers are done for a specific purpose (not gambling, drugs, etc.) – as providers, at times, knowingly or unknowingly, misrepresent types of accounts and their purpose. Even when discussing a renewal of credit commitments for XYZ, a topic seemingly far away from a nature of cross-border transfers, about a third of our banking peers decline to join our bank due to potential regulatory concerns.”

Up to this point, de-risking has primarily impacted the smallest MTOs, cryptocurrency exchanges, and a handful of high-risk destinations such as Somalia or the Cayman Islands. However, even for the most prominent money transfer specialists, it remains a significant concern. Most of them have a primary banking partner but also maintain some business relationship with another major bank as a precautionary measure.

Banks regularly audit remittance providers using their services to mitigate regulatory exposure. Consequently, many bank employees understand how remittance specialists operate, whether Western Union or Wise. If the banks’ senior leadership were inclined to do so, it would be relatively straightforward for their money transfer managers to replicate “best practices” and concentrate on consumer remittances. However, this isn’t the direction they choose to pursue.

Banks’ Strategy for Money Transfers

There are three go-to-market models for banks in remittances:

- Ignore: most banks only offer wire transfers.

- Prioritize: build a separate money transfer business.

- Partner: rely on a specialist to serve your customers.

Banks’ partnerships with incumbent MTOs or fintechs have existed for many years. In 2016, claiming it was a minor bottom-up experiment, TransferWise signed up two inconsequential-at-the-time banks, N26 and LHV. It signed just one more in 2017 (Starling). In 2018, Transferwise raised stakes and created a stand-alone global partnership team while launching an API portal. That year, it lost Starling and gained Monzo:

In July 2018, Transferwise signed its first partnership agreement with a large bank, BPCE, but it never went into production. In 2019, Transferwise signed up a few more tiny banks in the US and Australia. Afterward, the pace started to pick up. By early 2024, Wise Platform had agreements with over 85 partners representing 10 million customers and businesses (N26 and Monzo have grown significantly since the signing of these agreements). Some partners even claim a 15% penetration, but assuming an average 5% penetration, this line of business might already contribute 5-10% of Wise’s active customers. Wise expects most of its volume to come through its Platform business one day.

Unsurprisingly, the world’s largest banks have ignored such partnerships because they are unconcerned about disruption, while smaller banks typically do not have customers with such needs. For example, in the US, only about 10% of banks offer international money transfer services for their customers. Ironically, instead of JP Morgan Chase using Wise as a white-label solution for money transfers, Wise was the first to use Chase to offer interest-bearing accounts.

Who is using banks for money transfers?

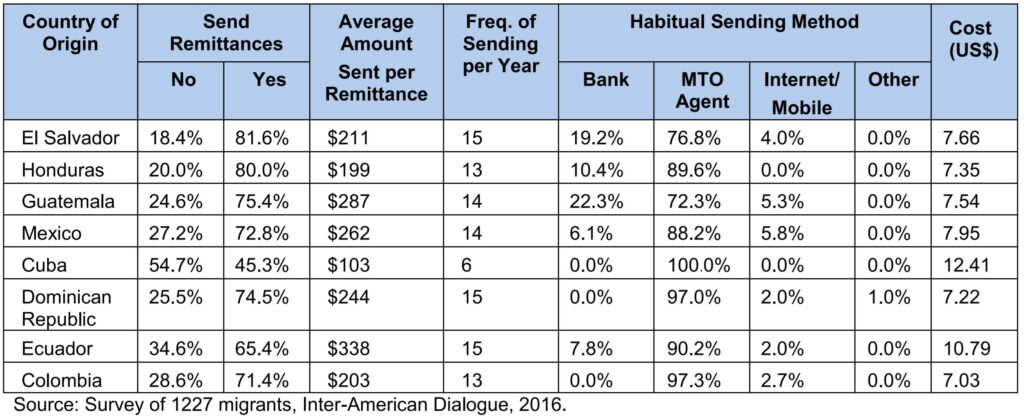

Banks are used for international money transfers by all consumer segments, including recent migrants.

Until about a decade ago, migrants relied even more on banks for cross-border transfers. However, providers like Western Union and Xoom began offering digital services. Despite this, the volume of money transfers going through banks continued to increase as more migrants came to the US and opened bank accounts:

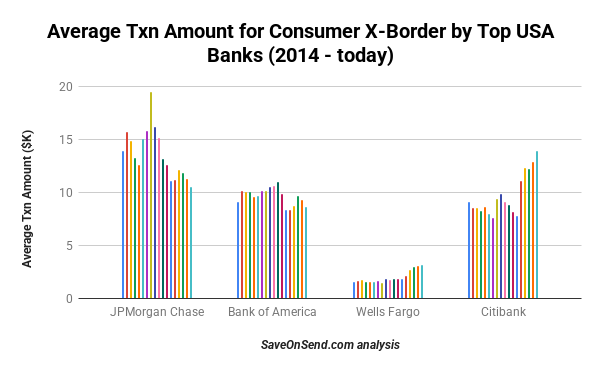

However, the typical users of money transfer services at banks differ from the customers of MTOs and fintechs. Let’s review the average transfer amounts (in thousands of dollars) among top banks:

Compare this with the average principal amount of remittances sent offline (via a cash agent): $200-400, and digitally: $1,000-2,000.

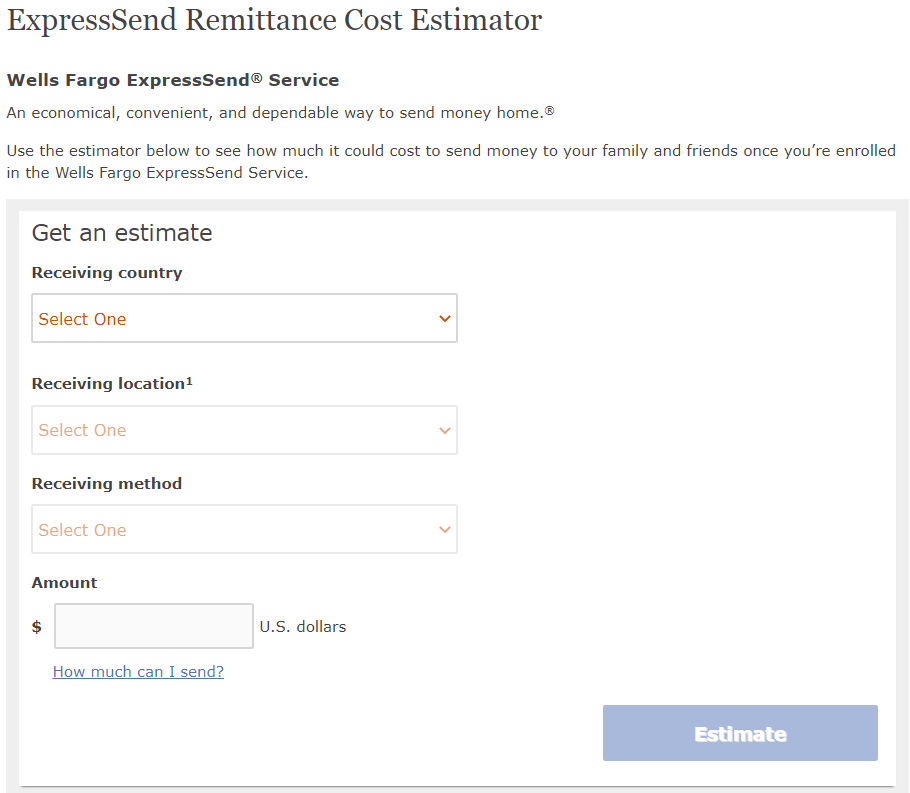

Banks’ primary consumer sub-segment is different: less frequent senders who remit much larger amounts and use wire transfer methods for sending money. But why does the average transaction size for Wells Fargo differ so significantly? It is the only US bank that actively targets traditional remittance consumers among its customers, with a dedicated product launched in 1994 and a separate landing page launched in 2007:

While performing well overall, Wells Fargo has been particularly successful in the USA-to-Philippines corridor, where it ranks among the top 5 digital remittance providers, despite charging above-average margins.

Banks’ pricing for money transfers

Traditional bank services for money transfers tend to be expensive. TransferWise even claimed that banks are 10 times more expensive.

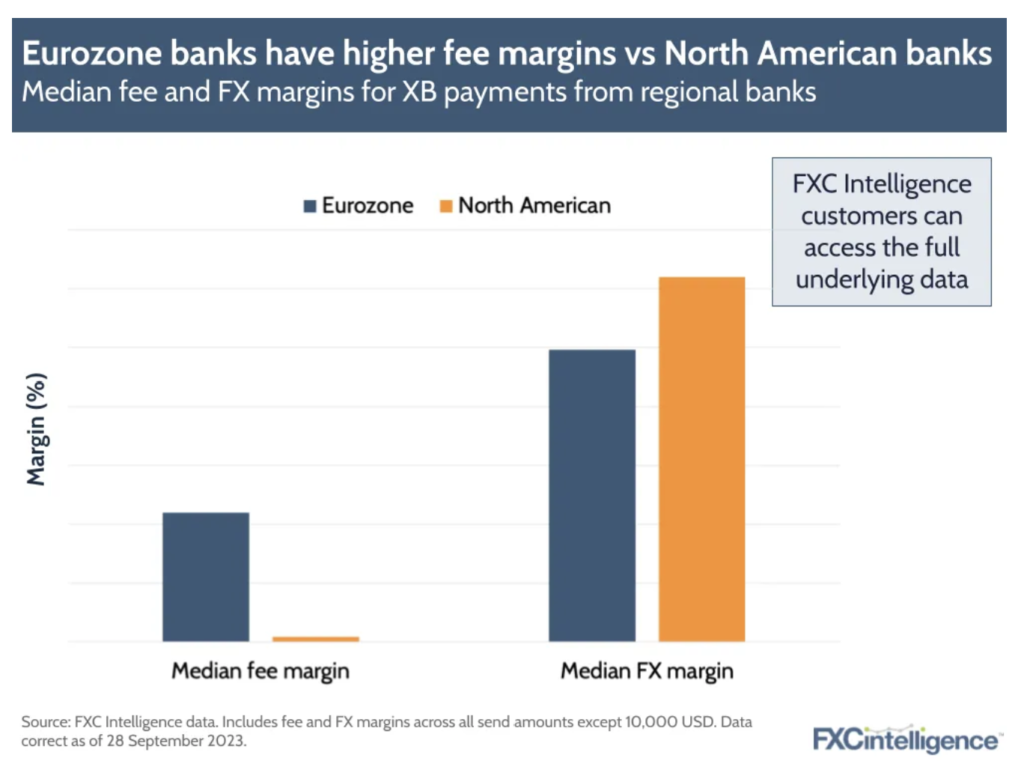

Those claims were misleading (see this SaveOnSend article for more), but the pricing gap between traditional banks and money transfer specialists remains substantial. This is primarily due to banks’ worse foreign exchange rates, which can be less transparent to customers than fees. However, there is a difference in how banks make money on cross-border transfers in Europe compared to North America. In Europe, banks charge much higher fees, while in North America, they charge more in the FX markup.

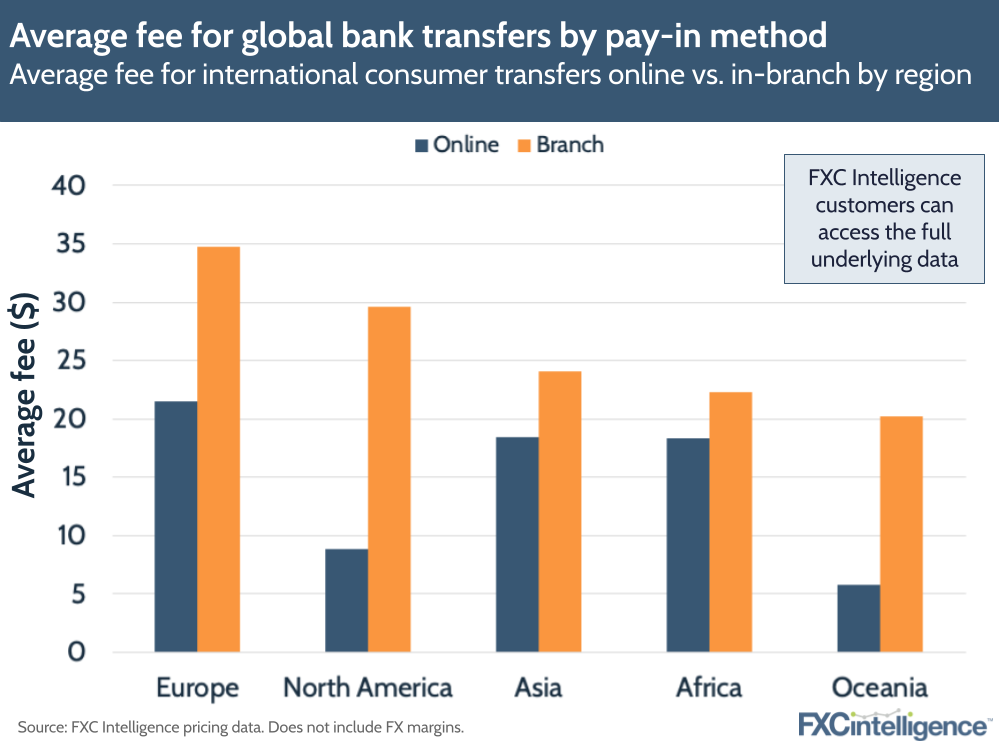

Historically, banks have charged fees ranging from $25 to $50 for wire transfers. However, the competition from fintech companies and the cost advantages of digital channels have resulted in considerably lower prices for online transfers than in-branch service.

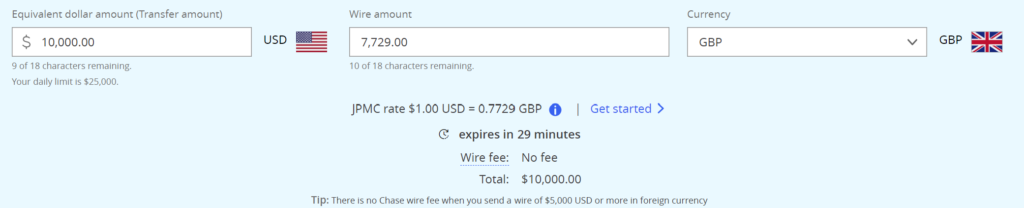

Banks may not charge fees for higher-volume transfers. For example, JP Morgan Chase, the largest retail bank in the US, for instance, doesn’t charge a fee for wire transfers exceeding $5,000:

When banks conduct international money transfers at rates 2-3% less favorable than the market rate, it is easy to eliminate visible fees. An average transfer of $10,000 translates to $200-300 in revenue per transaction through a low-cost digital channel. Not a bad business.

Do customers like their bank?

What about the quality of service for cross-border customers in those banks? It’s a common belief that consumers have a negative view of their banks, with a cliche suggesting that millennials would prefer a root canal over dealing with a banker. In reality, among millennials, satisfaction with a bank’s branch experience exceeds 80%. On the other hand, a sleek online interface might be perceived as less trustworthy when sending money.

It could even be argued that consumers strongly like their banks. Just how strong is this affinity? Take Wells Fargo, for example, which was embroiled in multiple public scandals, including the opening of fake accounts and withholding insurance refunds. Did the bank’s customers shift their business to any of the thousand other banks or opt for a trendy fintech startup? Nope, they stuck with Wells Fargo:

Moreover, migrants tend to exhibit a strong loyalty to banks from their home countries that offer services in the host countries. PNB is the 5th largest bank in the Philippines and plays a significant role. Similarly, ICICI and IndusInd banks, ranked #2 and #6 in India, continue to be active players for transfers from the US to India.

Banks’ service quality

Similar to US banks, the remittance portals of many non-US banks (PNB, ICICI, IndusInd) appear to be outdated by ten to twenty years. Given the superior digital capabilities and pricing offered by MTOs and fintech players, it can be perplexing that these banks continue to attract remittance business. However, this backwardness may evoke a sense of tradition and stability for some customers.

While Wells Fargo stands out among the largest US banks for its comprehensive approach to targeting typical remittances, other banks may also engage selectively. For instance, India is not only the world’s largest recipient of remittances, but its citizens in the US tend to be more digitally savvy than other large migrant groups. Consequently, Citibank has created a dedicated global landing page tailored to this niche.

Banks’ attempts to build money transfer fintech

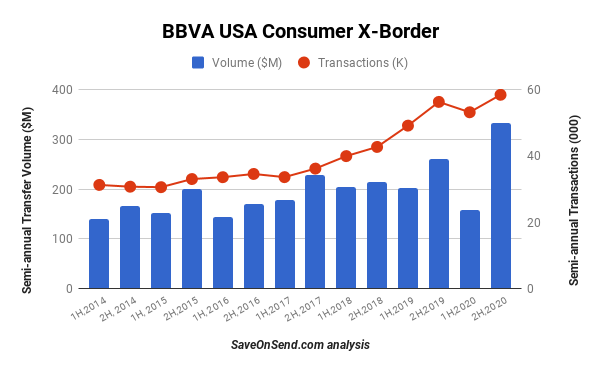

Only a handful of banks have established separate fintech subsidiaries dedicated to cross-border money transfers. This approach allowed them to explore digital technologies without risking their primary brand. A case in point was BBVA Compass in the US, formerly a subsidiary of BBVA. It strongly emphasized Latin American markets and ranked among the top thirty US banks in consumer cross-border volume. However, a notable decline in cross-border volumes in 2016 prompted the bank’s executives to prioritize the cross-border consumer business within their overall strategy.

Renowned for its innovative culture, BBVA made a significant move in October 2017 by launching a dedicated mobile remittance application. The bank commenced with the USA-to-Mexico corridor and named the app Tuyyo, which translates to ‘you and I.’ The app offered a basic user interface and had limited features.

The bank continued to charge an above-average margin, approximately 3% in total, with half of it coming from a fee and the other half from a foreign exchange markup. Despite an extensive PR campaign, six months after its launch, the app had minimal downloads:

Less than two years after the launch, it became apparent that the app couldn’t compete with the leading fintech players in this space, and BBVA announced the shutdown of its services.

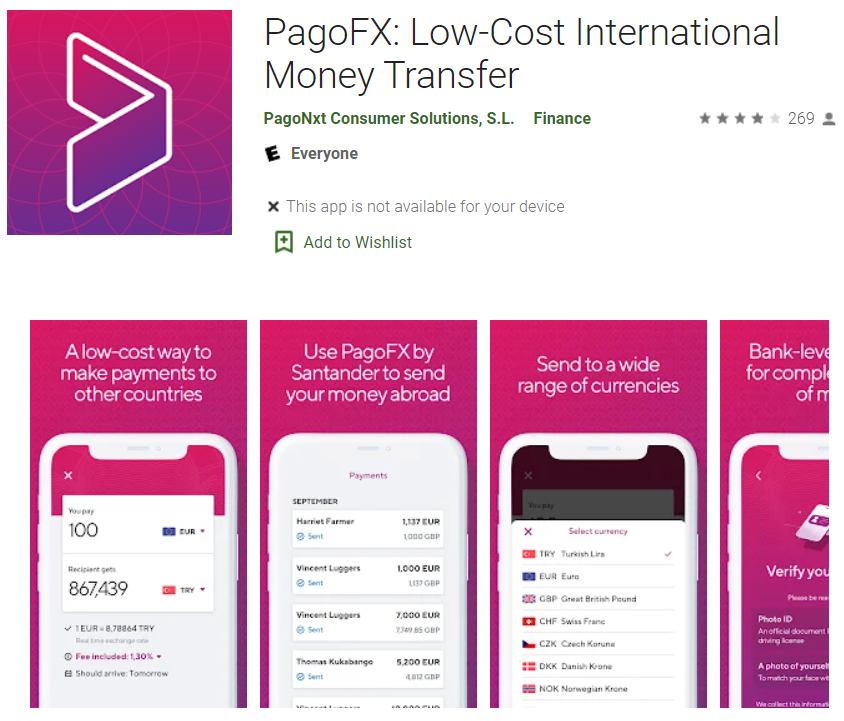

The same fate awaited another Spain-based bank with a global reach, Santander. In April 2020, the bank launched PagoFx, a Wise wannabe:

Santander took only 15 months to shut down PagoFx for remittances and pivot to business payments as PagoNxt. Banks repeatedly failed to grasp that taking market share from specialists is a magnitude more challenging than satisfying existing customers with enhanced digital user experiences.

In 2020, it looked like HSBC had learned from the failures of others when it launched its version of Revolut’s multi-currency cross-border wallet, which is only for existing customers and does not have separate branding.

But no, HSBC also couldn’t resist making the same mistake in 2024 by launching a different brand, Zing, to target external consumers:

Why would consumers who are happy with Wise and Western Union or their bank’s money transfer flock to HSBC? Those young professionals supposedly dream of becoming “Founder Members” of Zing and getting a limited-edition debit card.

A year later, Zing was shut down. The results were okay in one regard. According to Financial News, HSBC’s Zing acquired 9,000 monthly users out of 131 thousand customers. The shocking part was spending two years and $100M in preparation while hiring 400 employees. What is even worse, HSBC decided to blitz scale across multiple products and 100 corridors—yet, according to the Financial News, failing to prioritize fraud controls in its home country:

Project Green was designed to enhance Zing’s fraud controls, align with regulatory requirements and HSBC’s anti-money laundering policies, and establish a framework for monitoring transactions, according to internal documents.

The overhaul began last summer, when staff were informed that Zing was focusing its resources on the UK market and fixing issues highlighted by the audits, a person familiar with the matter said.

Some staff working on international expansion were subsequently reassigned to work on Project Green and have not been moved back, the person added.

However, even if HSBC’s Zing had been competent in strategy, marketing, and compliance, its setup doomed it. Banks have a long history of failing to scale fintech subsidiaries under separate brands—especially in the unforgiving cross-border consumer transfer space. Rather than leveraging its $11B in C2C x-border transfer volumes in its core business, HSBC repeated the same mistakes as BBVA and Santander before.

Zing will be remembered as yet another extravagant attempt by a bank to cosplay as a fintech—burning through resources with hundreds of employees, lavish referral bonuses, and traditional advertising, all while launching at a breakneck pace rivaling fintechs that took 5–10 years to expand. Contrast that with Wise and Revolut, which raised $1.7B over many years by consistently achieving groundbreaking milestones. For instance, Wise secured just $100M over six rounds spanning five years—by which point, it was already surpassing Western Union Digital and Intermex in volume.

Conclusion

As a class, banks will continue to play a significant role in cross-border money transfers. While they may not view remittances as a strategic product that warrants a fight for a bigger market share, banks will always remain attentive and invest just enough in their money transfer services to satisfy customer needs. In rare cases, they may proactively target niche markets with significant growth opportunities. Instead of banks worrying about competition from money transfer specialists, including fintechs, these players have significant concerns if banks discontinue offering them correspondent banking services.

Thank you for taking the time to read our analysis. We continually update our articles on our blog, so we encourage you to return regularly. If you have any concerns about the accuracy or objectivity of our facts and conclusions, we welcome your feedback in the comments section below.